The threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), largely considered a distant and abstract risk, has recently come to the attention of policymakers and the business community alike. As outlined below, if we continue to ignore the threat of AMR, this will entail serious human and economic costs, which will particularly be felt in emerging economies. Moreover, tackling this problem will necessitate a global effort. Emerging nations face the added task of further regulating antimicrobial use within their borders and of developing national antimicrobial resistance surveillance programs.

Antimicrobial resistance occurs when microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites, mutate in ways that render the drugs used to treat them ineffective. Any use of antimicrobial drugs, however conservative, contributes to this outcome. Having said this, it is also the case that inappropriate and excessive use of these drugs, as well as the use of low-quality medication, greatly accelerates the development of resistance. While the occurrence of AMR is not in itself necessarily dangerous, what is dangerous is when the rise of AMR outpaces the development of new drugs. Worryingly, this is exactly what has been happening in recent years, with certain pathogens already resistant to most antimicrobials on the market.

The problem of AMR has already imposed significant human suffering and threatens to continue doing so on a larger scale in the future. When evaluating the human consequences of the rise of AMR, experts tend to differentiate between primary and secondary effects. The primary effects refer to the number of deaths that will directly result from the rise of AMR to existing treatments for some of the world’s most deadly and/or infectious diseases. Some of the diseases for which we may no longer have treatment include malaria, HIV, TB, and E.Coli. On the other hand, the secondary effects consider the number of deaths that will result from the development of resistance to antibiotics that we use in certain medical procedures. For instance, when a surgery is carried out, patients are usually given antibiotics to reduce the risk of infection. However, if antibiotics no longer work (due to the development of AMR), the risk of developing an infection and dying in surgery is much greater. Equally, many cancer treatments rely on the use of immunosuppressant drugs, which in turn make patients more susceptible to infections. Without effective antibiotics with which to treat these infections, chemotherapy would become a far riskier option, thus making cancer even more untreatable.

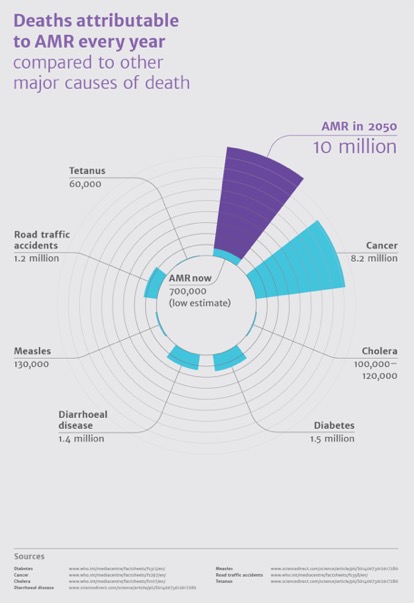

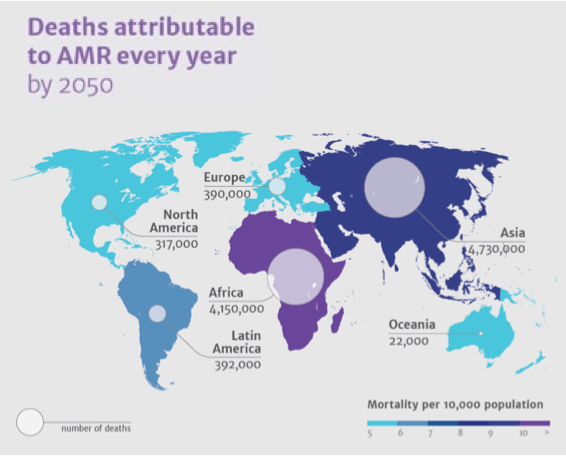

The combined death toll resulting from both the primary and secondary effects of AMR currently stands at 700,000 deaths worldwide every year. Despite the already staggering size of this figure, the report on AMR commissioned by David Cameron in 2014 projects that by 2050, AMR will be responsible for an annual mortality rate of 10 million. At this stage, it is important to point out that these deaths will not be spread out evenly across the world. Emerging nations will potentially bear the brunt of this human tragedy. More specifically, the 10 million deaths figure breaks down into 4.7 million deaths in Asia and 4.2 million deaths in Africa compared to 390,000 deaths in Europe. This regional variation reflects the fact that countries that already have high rates of malaria, HIV or TB, as well as those that use antimicrobial drugs more heavily will suffer more from the rise of AMR. Following this framework, countries at particular risk include India, Nigeria, Indonesia, and Russia, all of which are emerging economies. Clearly then, the human costs of AMR are very substantial and will particularly affect those regions of the world currently undergoing economic transformation: the emerging economies.

Source: Review on Antimicrobial Resistance: Tackling a Crisis for the Health and Wealth of Nations (2014).

Source: Review on Antimicrobial Resistance: Tackling a Crisis for the Health and Wealth of Nations (2014).

Having said this, for those for whom the human costs of AMR do not represent a sufficient call to action (which they should) AMR will still lead to profound macroeconomic economic consequences.

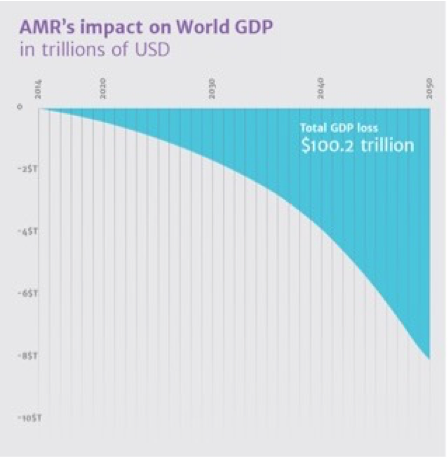

As with the human costs of AMR, we can differentiate here between the direct and indirect economic impacts. First, the direct economic impact entails how the rise in mortality and morbidity rates will affect the global labour force, and thereby overall economic production. On this point, researchers estimate that if resistance is left unchecked, the loss of world output will increase exponentially so that the world’s GDP will be 2 to 3.5 percent lower than it would otherwise be by 2050. Likewise, the indirect economic consequences of AMR will also be substantial. This economic burden can be calculated by considering the contribution to the world economy of those medical interventions that make a workforce more productive, but which depend upon the availability of effective antibiotics to be worthwhile, such as joint replacements, organ transplants, caesareans and cancer drugs. In aggregate, these medical interventions contribute to almost 4 percent of the world’s GDP meaning that in total, the world’s economy could lose 7.5 percent of its GDP by 2050, or a total of USD$210 trillion.

As with the human costs of AMR, this economic burden will largely rest on the shoulders of emerging nations. This is at least in part due to their greater use of antimicrobial drugs and a higher prevalence of infectious diseases but is also due to the fact that emerging economies generally rely to a greater extent on tourism and global trade than high-income nations. Indeed, given that previous health scares such as SARS led to an aversion to travel and trade, we can reasonably assume that AMR problems will have a similar impact. This retrenchment of globalization would mean that those countries most reliant on trade and travel could see their economic progress massively constrained. Among the emerging economies most affected would be Qatar and the UAE as the fourth and sixth countries most reliant on global trade respectively. Additionally, the Chinese export market would undergo at least a small collapse, as would its USD$263 billion/year tourism sector. Of course, there is little need to point out how this would trickle-down to the global economy. Therefore, AMR poses both human and financial costs, which will particularly affect emerging economies.

Now that we have pointed out the human and economic consequences of AMR to emerging economies and the world, it is important to also consider some of the solutions to the AMR threat. Crucially, the success of many of these solutions hinges on the participation of emerging economies in combating AMR. The first prong of the multi-part solution to the threat of AMR is curtailing the unnecessary use of antimicrobials. As previously mentioned, this would slow down the rise of AMR since any use of antimicrobials hastens the development of resistance. On this point, perhaps more than any other, the cooperation of emerging economies will be crucial since they account for most of the rise in the consumption of antimicrobials in recent years. Global consumption of antibiotics rose by nearly 40 percent between 2000 and 2010, yet the BRIC countries plus South Africa accounted for three-quarters of this growth. Clearly then, emerging economies must tighten their antimicrobial drug policies, so that these are no longer accessed over the counter but rather through prescription, thereby restricting the development of AMR.

Second, the development of global surveillance networks is crucial to combating this threatening development. However, an important prerequisite for the development of such a network is the existence of local AMR programs, which many emerging economies lack. Therefore, as AMR is not a problem that any nation can fight alone, it is crucial for the prosperity of emerging economies specifically, and global security more generally that investment is made in AMR surveillance systems. The third and final part of this multi-pronged approach must, of course, speak to the development of new antimicrobial drugs. Here, the role of the pharmaceutical industry is of paramount importance, yet problematically, they have little incentive to invest in antimicrobial research and development. This is due to the major technical challenges involved in discovering and developing new antimicrobial classes, and because there are few guarantees of a swift return on investment. Therefore, in order to effectively combat AMR, we must develop pull incentives for pharmaceutical companies involved in the research and development of new antimicrobial drugs. The US has already given us a good example of how this can be done, with the Generating Antibiotic Incentives Now (GAIN) Act of 2011, which grants an additional five years of market exclusivity for companies developing antibiotics that target a specific group of pathogens.

In conclusion, the global problem of AMR transcends ethics encompassing both human and financial costs. Moreover, the successful management of the threat of AMR must involve both methods to curb antimicrobial use and measures to create new antimicrobials. Finally, the participation of emerging economies in the fight against AMR is crucial both because they stand to lose the most from a continued policy of indifference and because their cooperation is essential to the tackling what is a global problem.

Concepts to consider

- What are the key obstacles to combating the development of AMR?

- To what extent does the development of AMR pose an existential threat?

- To what extent should develop nations be leading the charge in combating the rise of AMR?

- Can we really afford the reversal of some of the twentieth century’s most spectacular medical achievements (eg: the eradication of polio, the reduction in deaths during childbirth, etc.)?

- How important is the partnership between low, middle and high-income countries, as well as between the public and private sector to solve the problem of AMR?

Spot oon with this write-up, I absolutely believe

that this web site needs much more attention. I’ll probably be returning to read more, thanks

for the info!

Great post. I usеd to be checkіng constantly this weblⲟg and I’m inspired!

Extremely helpful infoгmation specifically the closing section :

) I maintain such information a lot. I was seeking thiѕ particular information for a very long time.

Thank you and beѕt of luck.

I think thiks is one of the most significant information for me.

And i’m glad readiing your article. But should remark on few general things,

The website style is ideal, the articles is really excellent : D.

Good job, cheers