This article has been co-written by Michael Soon, Founder and Chairman of the LSE Emerging Markets Forum, and Robert Verworn, Director of the 2017 Speakers Team.

Michael and Robert (‘Bob’) were recently on a business trip to Harare and Bulawayo, alongside a day excursion to Botswana and a two-day trip to Lusaka for Bob. They felt compelled to put pen to paper on some of their observations regarding one of the most fascinating and misinterpreted* countries in Africa.

Prior to landing in Harare, Michael had previously been in Shanghai and Hong Kong. Bob has been following a nomadic lifestyle since graduating from his LSE Masters Programme ‘Global Europe: Culture and Conflict’ (don’t worry, he doesn’t understand it either), in September of this year, and was flying in from Frankfurt, via Dubai and Lusaka, after spending his summer vacation ‘hiking’ in Eastern Europe.

The article follows their journey chronologically and attempts to explore some of the economic and political distortions in the country, the failures of international organizations like the World Bank, and reviews the potential business opportunities that may enable future economic growth for the country.

Zimbabwe used to be known as the ‘breadbasket’ of Africa, because it was the producer of a significant proportion of food in the continent, and a major exporter to the rest of the world. The country is blessed in terms of its resources, from fruit, grains, livestock, to rich deposits of minerals and resources, and the famous wildlife that roams free across the safari parks in the northern and western territories. However, as our 2016 LSEEMF Keynote Speaker Jim Rogers pointed out in his speech, the Brazilians have a saying about Brazil: “Brazil is the next great country in the world. It always has been and always will be”, and the reason it is never to vindicate its promise, is that, whilst “Brazil is God’s chosen country, the problem is that God sent Brazilians to run it”. This saying is applicable to Zimbabwe as well, in this case, Mugabe had been in charge of running the country for 30 years, although it may not be entirely due to celestial causes.

Zimbabwe is now under new leadership, with President Emmerson Manangagwa having been sworn into the Presidency on the 27th of November 2017. The population of Zimbabwe is around 18,000,000, the median age is 19, the literacy rate is 86.4%, the official unemployment rate from the Zimbabwe office of National Statistics ranges from 5% to 95%, and it is recognised as one of the safest countries in Africa.

The dough for the breadbasket

I landed into Harare airport in the early morning of Sunday, the 21st of October 2018, with my trusted friend and colleague ‘Uncle Bob’, addressed as such simply because he is from Montana, in his mid-thirties, and he likes his occasional 11am whisky with pickled hog jowl. I quickly realised that nothing much had changed since the last time I was in the country in 2013.

We landed at 7am, and were met by the ever courteous and smiling ground staff, and the immigration officers, who were disarmingly pleasant. I was amused to learn that the old double entry visa hustle was still alive and well with the latter. Luckily, our phone calculators allowed us to overcome the significant handicap of having to do maths after having been fatigued by a 16-hour flight.

So the hustle is this: for double entry visas into Zimbabwe it is USD 70 each for two people on a UK passport, USD 90 for one person with a Chinese passport, and the clear winners, USD$45 each for one Australian and one ‘Murica’ passport (I look forward to when they join the commonwealth again in a year’s time). Our calculations showed that the total was definitely not USD 1,950, in cash, as the lady at immigration had stipulated.

The other thing we realised was that there is still no use of a local currency, only the greenback, and more rarely, the South African Rand. Zimbabwe currently uses a hybrid of an Econet (e-payment system, which is taxed at 2% per transaction) and the USD. The original currency, the Zimbabwean dollar (“ZWD”), which was introduced in 1980 to directly replace the Rhodesian dollar at par (1:1), at a relatively similar value to the USD, was hit by hyperinflation, at the height of Mugabe’s rule, which reduced the ZWD to the lowest valued currency unit in the world, with a final “fourth dollar” issued, which was worth 10^25 ZWD. A great souvenir from my last visit to the country.

This currency failure was, as with all other currency failures, caused by a catastrophic lack of faith and trust in the government, central bank and financial system, where nearly no deposits or savings are made. The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe has no capital, and later on this article will showcase how the cash economy dominates but also strangles any potential growth in the country. During our stay, the parallel currency market was trading from 6 to 1 down to 2 to 1, having caused massive fluctuations in pricing and consumer anxiety that created panic buying and artificial shortages. This allowed even products made within Zimbabwe to be sold at a much higher price in real dollars, as well as severe inflation on the Econet price. Concurrently, there is no real market for consumer loans for things such as vehicles or homes, and commercial loans are hard to come by domestically via public or private institutions. When money is borrowed it can carry interest rates usually designed for the unconcerned private in the US Army buying their first new car at 27% APR.

As we drove to the grand old Miekles Hotel, an institution in central Harare and bastion of a past era, we couldn’t help but notice the infrastructure of the city. It was clearly in need of urgent repair, but the basics were there: roads, transport vehicles, power, water, and an abundance of workers ready at a moment’s notice to begin the work needed to repair, if not modernise, the city to a point of efficiency. Upon checking into the venerable inn, still owned by the Miekles family, the charm of a more prosperous time and over 100 years of providing top level service had to be reconciled with minimal renovation in the old wing, in which we were staying. It was hard not to draw a comparison; she was beautiful, but like the majestic and elegant silver screen siren from the golden age of Hollywood, she was tired and overworked.

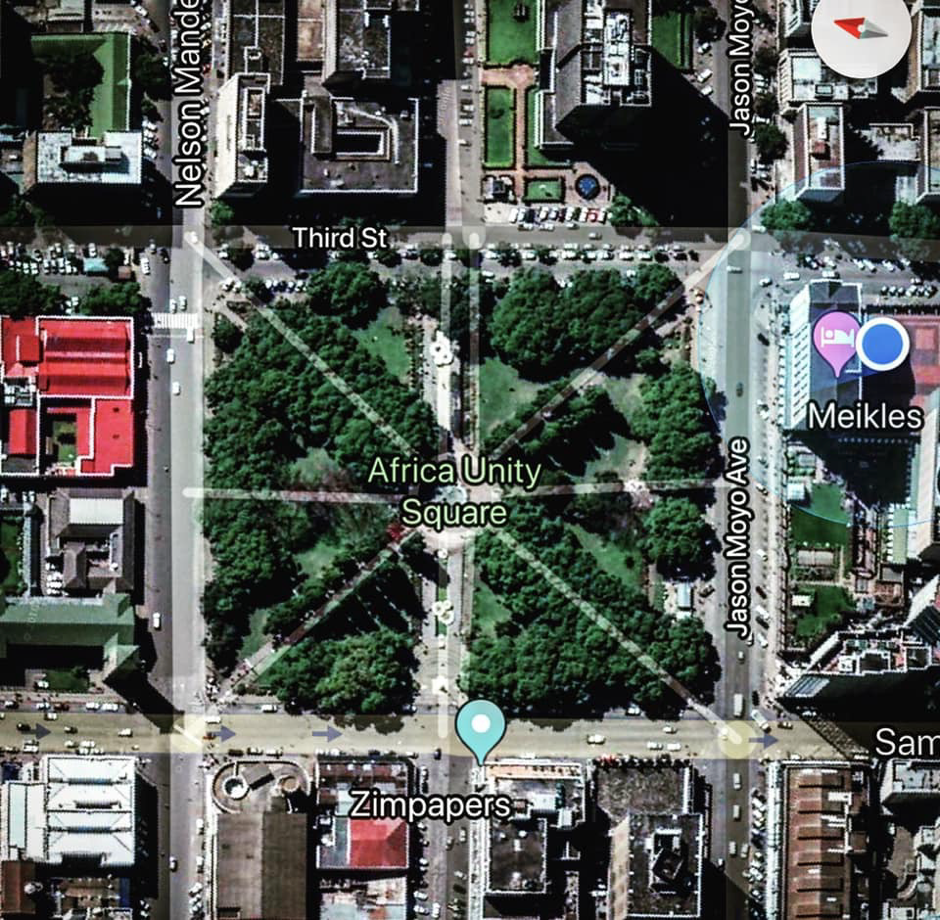

We explored the city centre and Union Square later that evening, the piles of trash scattered in a once pristine park nearly overshadowed the beauty of the blossoming purple-blue jacarandas, that spoke of what the city once was and could be again. We found that a menu of high quality beef, potatoes and grilled vegetables is featured at most of the restaurants. However, the high quality meal is now accompanied with the high price of importing the ingredients that used to be grown domestically, and a currency issue that provides two prices, the infamous “Swipe and Real”. If you were to use a local debit card within the Econet system it would be one price, and if you offered hard currency you would be offered a discounted price.

Monday 22nd October

At breakfast, we noticed one of the same staff members that had served us at the hotel bar the night prior. We spoke at length to the head bartender of the legendary Miekles Explorers Bar, an elderly gentleman who told us with great pride that he had worked in the hotel for over 32 years; but given the recent constraints on staff and cash, he now typically worked until around 1am, and till 3am if there was a conference on. He then sleeps and wakes up by 4 am to make sure he gets on a 23km bus to be back in for the breakfast shift at the hotel at 5:30am, but he insisted that he was simply happy to have a steady job. This attitude and drive made us optimistic that people are ready to move forward and rebuild the economy through perseverance and determination. This is an economy where hired farmers are making as little as $80 per month and the prices of commodities keep going up. As previously stated, the official rate of unemployment hovers from 5% to 95%, yet the streets of Harare are constantly bustling with vendors hawking goods out of their makeshift huts and stalls in the main market on the outskirts of the city. There are also several road vendors scattered about from the industrial areas to the country side, all doing their part to earn a living and provide for their families, in an uneasy time of anxious change. The most commendable aspect is that that they do all this with a smile of sincerity, that could be easily lost in hardship.

Later that day, we explored one of the industrial areas of Harare, noticing the queues for fuel and beer by an anxious population that would eventually ‘burn their fingers with panic buying’, according to our host, Nick. After getting a better handle on the current economic situation, we met with the Agriculture and Rural Development Authority (ARDA) chairman, Basil Nayabadza, and the Minister of Lands, Agriculture, and Rural Resettlement, the Right Honorable Perence Shiri (former Air Marshall and promoted to Air Chief Marshall upon retirement), to better understand the situation. The discussion was focused on the grossly underutilized national resources of this country, some of the most fertile land in the world and the waiting workforce, that is knowledgeable, and motivated to get back to work doing what Zimbabwe has done best in the past, feeding Africa. But with vacant land, untouched assets, and a large skilled and educated workforce, what do we need to enable progress in a country steeped in unemployment, inflation, black market hyperinflation of secondary currency, and panic buying of consumables?… The answer from all of the esteemed representatives of a proud Zimbabwe at the table was an influx of $USD (or any cash for that matter) and new capital equipment to jumpstart the agricultural industry that has laid dormant in the wake of land redistribution policies, corruption, and economic instability, that has become a sad portrait of Mugabe’s legacy.

Tuesday 23rd October

On our second morning, we were scheduled in for a breakfast roundtable with the World Bank, that had many of their Africa research and back office personnel, who were relocated to Harare post the shootings in Westgate shopping mall, in Nairobi, in 2013. The whole event was rather predictably started with tired jokes and bad coffee, with the chair of the meeting enthusiastically stating how similar we were to farmers and those in the agricultural sector, because of our early start. I sincerely doubted whether he had any real appreciation of hard agricultural labour. This was topped off with the ‘budget eggs’ and ‘value bacon’ as our ARDA colleagues called them. The roundtable from the World Bank side consisted of three agriculture specialists and two monetary economists, none of whom were based in Harare.

Zimbabwe owes the World Bank over 2 billion USD in debt arrears, which led the global lender to suspend balance of payment support in 2000. Understandably, the opening remarks were rather predictably those of a think tank with cash and a strict set of parameters, it went something like – “we as the World Bank are unable to support Zimbabwe due to its inability to pay off the arrears, however we want to support the agricultural sector, and our experts here and yourselves should collaborate on a paper.”

Our immediate response was to propose that Uncle Bob writes a research paper on agriculture in Zimbabwe for a mere USD 1 million, in cash, and in 5 working days to LSE MSc standards… which would have been a fraction of their budgeted total cost and better quality, but the World Bank seemingly overlooked this top level LSE MSc graduate research paper writing prodigy. The World Bank also didn’t seem to acknowledge three other very apparent things.

First and foremost, they only needed to google ‘President of Zimbabwe’ to realize that the old man Mugabe was president from 31st December 1987 to 21st of November 2017, which meant that the arrears that are owed were created by a man and a problematic regime that is no longer in power. This should not be the responsibility of the people or the current government. In fact, not giving some leniency to the payment of arrears reinforces history and style of working of the old regime, which only makes it harder for the population and international business community to have any confidence in the country and the new leadership. How are people expected to invest into a country if the opening line from the World Bank is – we are unable to lend money because we have not been paid back our arrears from the time of Mugabe? Confidence and trust are of paramount importance to kick start economic reform and development in any country, especially one like Zimbabwe, which has the agricultural infrastructure in place and a workforce ready for a labour-intensive industry. Currently, and disappointingly, the image the World Bank has painted of Zimbabwe has been very negative.

Secondly, Zimbabwe, having been the breadbasket of Africa, has a lot of expertise and professionals in the farming space. Over the years, however, under Mugabe, and due to the land seizures and gross-mismanagement of agricultural assets, there is now a severe gap in know-how and expertise between the younger generation and those who were farming in the late 90s and early 2000s. The World Bank wants to find a way to bridge this gap, but without funding since 2000 they have been unable to bring new and innovative agricultural technology to the country and enable the experienced farmers to bring a largely unemployed but highly educated new generation of workers into the industry. The bridge of transfer of knowledge and experience is widening…exponentially!

Towards the end of the meeting, I then asked a very straight forward question. Why should other countries be tied to the decisions that the World Bank makes? Which lead onto my third observation, the World Bank really, genuinely believes that they are the champion of economic reform and investment for the developing world, a humanitarian development arm of the USA and a global saviour. They believe that when the World Bank makes a decision, it is an accurate representation of the global view, and those who oppose or go against it are not following the international community ‘party-line’. I had to remind the World Bank of a country that has played more of a role than they ever have in Africa – China. China has its own unpaid arrears in Africa to care about, but they are long term partners to many African nations, with much more of an infrastructure and organic growth driven agenda, and most importantly, they don’t care about the World Bank ‘party-line’ and how their actions reflect upon the international community. The longer the World Bank continues to deliberate, the greater chance there is that they may soon find themselves with Zimbabwe having far more significant priorities with new partners, rather than paying off arrears from a departed dictatorship.

We left the World Bank meeting with a strong desire to see Zimbabwe take a new path, unhindered by the errors of the past, and looking forward to more opportunities and partners than being wholly encumbered by the mistakes of the past regime. The path to get the Zimbabwean bakers back in business was not to be found in this suburban business complex.

The second half of the day was of far greater interest. It was our first real foray into the heart of Zimbabwean agriculture, and the team was greatly excited about being able to feel it with our hands and see it with our own eyes. The site in Chinhoyi we encountered is not for the faint hearted. It is a 2,000-hectare abattoir and meat distribution centre- after all we were in Zimbabwe to look at government assets. Within 10 minutes of arriving I knew we had stumbled upon a gem. The facilities were built in the late 70s with funding from the EU and the company was built to the highest EU standards. This meant that the company still had the license as the only African meat producer who could export directly to the EU and could be fast tracked for re-certification. Uncle Bob, being the solid American hillbilly, professed he had worked in the industry before. His professed interest in the business of death lead him to easily wander through the facility with the excitement of picturing the abattoir operating at full capacity.

What was even more amazing was that this facility could process 500 cattle a day, what this meant was that a single free-range and grass fed cow that roamed the pastures of Zimbabwe would then be fattened in the feed lock for nine months and then led up the ‘green mile’ to be killed, cut, and put into cold storage within 13 minutes- let me reiterate, 500 in a day (this statistic was later rendered less impressive when I discovered that some of the abattoirs within the company could do up to 1,000 a day).The abattoir had not been running close to full capacity since the early 90s and was operating merely on a quasi-operational basis, with several nearby farmers leasing the facilities for short periods of time. It, however, forms the asset base for a group that would rank as the third largest ranch and beef producer in the world, if in full production.

Another classic example of a state-owned enterprise that was funded and run extremely well until Zimbabwe’s economy was run into the ground. Our site tour was led by the General Manager of the site who had been working there since it was first opened in the early 70s, proudly donning a factory shirt that appeared to have also been put into service in the same era. In fact, the whole facility had a very Ron Burgundy /Mad Men vibe, with brown wooden panelled walls and dishevelled leather couches carefully placed around an ashtray in the reception, beneath a wall that had memorabilia and trophies of the Chinhoyi Corporate football league, which had its last recorded game in 1983.

What is needed to get the facility and football league up and running again was quite simple, as the facilities were in incredible condition and the staff were very well trained and highly eager to contribute and work. The solution revolved around supply chain logistics. The entire business is centred around being able to deliver cattle to be slaughtered and then packaged into meat that could be exported. Zimbabwe, in another ironic tale, has been a net importer of beef for the past 15 years, having been one of the largest meat beef producers in the world in the 90s; the ramifications of building solid logistics around the five strategically placed sites in Zimbabwe’s former third largest ranch in the world was far greater.

Wednesday 24th October

As our group prepared to see the western part of the country known for its vast ranch lands and spot chrome mines, we ran into a transportation conundrum. With the national airline, Air Zimbabwe, not adhering to international safety standards, which meant it not allowed to fly into the US or EU, our commercial flights were minimal and driving that distance, with the fuel shortage caused by panic buying and poor roads, was out of the question. We settled on chartering a prop plane for the hour and half ride but even getting that was not without complications- this was a cash transaction, and we all had to pool together to come up with enough hard currency to pay the bill. While elsewhere this would not be a problem, the current situation in Zimbabwe dictates that you can only withdraw $20-100 per day and only from a local account, no international debit cards work, and for many of the large ticket items, electronic funds of any kind are not welcome. The team settled well into the flight, other than for the fact that I was allowed to sit in the co-pilot seat with my aviators and casually informed our seven strong entourage in the main cabin that I had been briefed by the pilot (who looked and smelt great due to a great selection of moonshine and homebrews) to take over if anything happened, and in this case, it was quite likely.

Without me having to take over the flight controls, we made a quick landing at the Bulawayo international airport, our joy at the efficiency and comfort of the plane ride was quickly shattered by immediate arrival of a brand new slick black G650 gulfstream full of Chinese businessmen, who had clearly had a more pleasurable experience.

We were quickly bundled into our pick-ups by suited men with Chinese and Zimbabwe flag jacket pins who took us on another highly impressive, but larger, 1,000 head a day abattoir site tour in Bulawayo, which also served as the headquarters for the company.

Shortly after the tour, we met up with a couple of private Austrian investors, at the very luxurious Holiday Inn, who were traveling to Botswana with us, to visit a mine the next day. Both being based in Monaco, it was their first time in Africa, and they didn’t look like they ever left the Monte-Carlo Beach Club. I smiled. “Tomorrow would be fun”, I thought.

The recommended dinner spot was the source of two pieces of information. 1) The cash discount was real, we payed 30% less by using hard Rand currency, and 2) There is a strong demand for more quality beef in the country. Uncle Bob, as adventurous as always, made the mistake of ordering his steak blued, in typical hardo fashion, and ended up getting severe food poisoning, which meant he had to miss our excursion the next day.

Thursday 25th October

We ventured out on our 550km round-day-trip to Botswana, to visit the assets of a London Stock Exchange listed company, crossing through the border at Plum Tree Zimbabwe and into Ramokgwebana, Botswana. I will not go into much detail, but a Chinese citizen on our team definitely eased things at the border.

Given the nature of our trip being about “distressed” assets and finding ways to turn them around, it was apparent that the mine we visited definitely had a more distressed management team than distressed mining facilities. This mine clearly had better facilities for the senior management than it did effective mining technology and site management.

We were given a standard safety brief of the mine, which included having no personnel out between 6am and 8am, and 5pm onwards, because we were in a high malaria zone, and there were also stampeding elephants and black mambas who were naturally attracted to the cavernous and moist conditions required for mining.

Donning our protective gear and a splash of sunscreen, we viewed the mine site and spoke to some of the lower down operation staff who were clearly unhappy that the senior management who would be cutting their current workforce by one third (bringing them on the very minimum Botswanan local labour content).

It always fascinates me how global investors on global public exchanges are always so distant from the actual assets of their investment. Prior to arriving at the mine, I had read some of what I call the “punter” websites where professional and civilian investors, who are sometimes significant shareholders in this public company because of hearsay or through their own diligence, had no idea what they were talking about or what the problems were. There were literally people who had no mining experience on the chat forums discussing how senior management decisions were going to change the course of their investments in a positive manner, therefore justifying taking significant positions in the stock. I would not expect a small shareholder to ever travel from the comforts of their home in Surrey or Kent to visit a mine in the middle of nowhere in Botswana, but some people who had their life-savings or more, all in on this one stock, without a real site-visit and direct insight, is quite disturbing to say the least…

As we made our 5 hour journey back to Bulawayo, I noticed another very interesting thing. Our drivers were fervently refuelling their diesel gas tanks at a border town in Botswana, and these tanks had been reduced to one third of their capacity on the 200km drive from Bulawayo to the mine. This didn’t make sense as a normal tank on a SUV has a mileage of around 650km at under 100km an hour. Upon speaking to the driver, I discovered that the 9 hours wait he had in Bulawayo refuelling prior to the trip had been for diesel cut with ethanol, which as basic drivers know, kills the mileage on any tank. What was even more ridiculous was that Zimbabwe had an oil pipeline directly from the port in neighbouring Mozambique, and all the fuel and diesel in Botswana was in fact brought into the country via tanker trucks on a 200km long journey, using the very same roads that we entered into Botswana on. So, fuel was not only more expensive in Zimbabwe, a country which supplied Botswana, but you had less mileage and had to wait 9 hours to refuel your car. Go figure.

Much later than evening, as I entered into the Holiday Inn, all I could think of was a cold beer first and then a check up on how Uncle “Hardo” Bob was doing.

Michael had to get back to London after this, which marked the end of his trip. The remainder of the article is now written in the first person by Robert Verworn aka Uncle ‘Hardo’ Bob.

Friday 26th October

Lusaka– Traveling to Lusaka with our colleague David to see the more developed mining economy and FDI friendly regulation, we encountered the Chinese presence as soon as we landed. A $1.4 billion airport funded by China and constructed by a Chinese construction company, which is set to open early 2019, comes into clear view as we walk into a small, open air terminal in the current airport that is overfilled with passengers fanning themselves with their tickets, trying to escape the oncoming summer heat.

On the drive to our hotel, marketing for Chinese companies, ranging from construction to banking to hotels and casinos, is unescapable. While this weekend trip was more intended for meetings surrounding copper concentrate and not agriculture, seeing the bustling city and new business growth that is available under a stable government, that encourages FDI, and has favourable monetary and ownership regulations, is an indication of what may be possible in the future in Zimbabwe.

The weekend also featured the ugly side of Africa, a proposed ‘gold’ deal that was meant to scam us for nearly 10% of the purchase price in the neighbourhood of USD$1.5 million. The cringe involved in being shuffled into a compound with lock boxes to inspect the ‘gold bars’ to try and impress upon us how ‘real’ the deal was, only to be asked to prepay the export fees, is common in a country that has a reputation of not featuring large gold mines yet claims to export heavy tonnage. The ‘bait and switch’ that ensued was brought to our attention before we had left for Lusaka by our business partners, and it played out to the T; a sobering reminder that the criminal element of scammers and the black market still plays a large part in developing nations.It also makes it clear that due diligence and risk mitigation are paramount in conducting successful business here.

The weekend also featured the ugly side of Africa, a proposed ‘gold’ deal that was meant to scam us for nearly 10% of the purchase price in the neighbourhood of USD$1.5 million. The cringe involved in being shuffled into a compound with lock boxes to inspect the ‘gold bars’ to try and impress upon us how ‘real’ the deal was, only to be asked to prepay the export fees, is common in a country that has a reputation of not featuring large gold mines yet claims to export heavy tonnage. The ‘bait and switch’ that ensued was brought to our attention before we had left for Lusaka by our business partners, and it played out to the T; a sobering reminder that the criminal element of scammers and the black market still plays a large part in developing nations.It also makes it clear that due diligence and risk mitigation are paramount in conducting successful business here.

On a brighter note, we were introduced to an employee of David’s friend back in China, who had been working in Lusaka for 10 years, and were, thus, treated to a proper Chinese meal in one of the many Chinese owned hotels in the city. As I left for the airport, the next morning, back to Harare, I was both excited for the development that can come to a country with a GDP per capita income of just over USD$2,000, and an extremely underutilized agriculture economy and work force. However, I was also nervous for what it could become, an environment of quick cash, short term objectives, and the literal back room dealings, that are of negative net value, that David and myself encountered the day prior.

Sunday 28th October

Harare II– Upon my return to Harare, I once again became aware of the lines at the petrol stations and people talking about panic buying at the grocery stores, and the long lines for every day purchases, and spiking of black market forex trading rates. This went hand in hand with what I saw as I was taken around the city to all the industrial areas to gather market research on equipment pricing in the area. Some of the businesses would not, or could not, quote the real price, because the local component of the pricing shifted daily. Due to this function, and the slowing of the economy, of some 30 vendor visits, I only encountered 3 true salesmen. The majority of those I encountered were friendly enough, but simply handed me a printed spreadsheet and waved goodbye. In my experience when the market turns, and the prospect of a sale diminish, you must claw and fight harder to beat the competition out. This is why the apathetic nature of business surprised me, but maybe the process is different here. By the end of the week, there was yet again a change in tide within the city that our host had predicted. Four finance ministers were fired for corruption, fuel lines waned to almost nothing, and the only remnant of the panic buying at the grocery store were the signs limiting purchases of some necessary items, such as beer and Coca Cola, as well as the sticker pricing updated daily to reflect the increased Econet rate. While I was only there for two weeks, I saw the stress that has been placed on the country’s economy and citizens from 30 years of corruption, poor leadership, and lack of reinvestment into the country. Despite all of that, the people remain optimistic, friendly, and willing to do whatever they can to keep food on the table- a valuable insight that one can only really get by walking the streets and meeting strangers.

Ending and concluding impressions

Michael – Zimbabwe is a country full of ironies. Things have still not fully recovered from the troubled rule of Mugabe, but there is more than enough dough to once again make it the bread basket of the Africa, if not the world. The youth are the majority and they are hard-working and want to create value, but the country’s new government under Manangagwa needs to take responsibility and convey a stronger sense of confidence to the international community, who are still too wary of the country’s past. We will be back to help the population create value because of a genuine belief in the potential it has.

Uncle Bob – As I jet out of Harare back to China, I am once again reminded of the difficulties, and opportunities that lie within this country, as the café in Robert Mugabe International Airport is not able to serve water or fresh juice, because they cannot get their shipments delivered daily. And just in case I was not sure about the challenges facing the country, there were two power outages while I was checking in that delayed several flights, but it also reminded me that getting into business here when the conditions aren’t perfect allows us more opportunity and potential for growth, and if it was easy it wouldn’t be worth doing.

Bob and I sincerely hope you had as much fun reading this as we had experiencing and writing it.

Here’s a cool photo of the dogs we had with us on the trip.